Table of Contents

From the first days of the full-scale conflict in Ukraine, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) and right-wing groups began so-called stabilization measures – a crackdown on Ukrainian citizens expressing dissent or suspected of having ties or sympathies with Russia. These measures encompass a wide range of actions: from preventative conversations to abductions, arrests, the initiation of criminal cases, torture, and even murder.

Official figures incited society to search for an internal enemy. The SBU created chatbots for submitting reports on “unreliable” neighbors and acquaintances, leading to the opening of criminal cases.

Below is a post by Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation, calling for reports on collaborators to the “ЄВорог” (e-Enemy) chatbot. Fedorov reports that in its first four months of operation, the chatbot received over 1800 reports about “lovers of the Russian world.”

In October 2022, the Daily Mail quoted Anton Gerashchenko, former Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, advisor to the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs, and initiator of the “Myrotvorets” (Peacemaker) website:

“Collaborators are being hunted, and their lives are not protected by law. Our special services are eliminating them, shooting them like pigs.”

While the exact number of people interrogated, held in basements, abducted by security forces, detained in illegal places of confinement, or killed remains unknown, the number of individuals imprisoned, in pre-trial detention centers, or facing criminal prosecution can be roughly estimated using publicly available information.

Trends in Criminal Proceedings

The number of criminal proceedings potentially related to views and opinions has been increasing in Ukraine since 2014. However, following the start of the full-scale conflict, the number of such cases has significantly increased.

According to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, at least 180,000 criminal proceedings have been initiated on articles related to the conflict* between 2022 and 2024 (see table at the end of the publication). It should be noted that, in some cases, multiple charges are filed against the same individual, but this figure reflects the number of people who have faced criminal prosecution in connection with the conflict.

For comparison, 54,000 such cases were initiated between 2014 and 2021. And only 310 in 2013, before the Maidan.

*Which Articles Are We Analyzing?

This analysis focuses on the main articles of the Ukrainian Criminal Code related to the conflict, excluding those directly related to combat actions – Articles 109, 110, 111, 113, 114, 258, 260, 332, 335, 336, 337, 402, 407, 408, 409, 436.

These are articles where accusations are often linked to the expression of views and opinions, unwillingness to fight, or the circumstances faced by civilians.

These include:

- Accusations of crimes against national security (Articles 109-114).

- Certain crimes against public safety – accusations of terrorism or participation in illegal armed groups (Articles 258, 260). These articles are often used to prosecute, for example, militia members, entrepreneurs in Russian-controlled regions who paid taxes in the region of their residence, or journalists on charges of “aiding terrorism.”

- Offenses related to illegal border crossing (Article 332) or assistance in such crossing. While penalties for the act of crossing itself are not severe, penalties for organizers are substantial.

- Various forms of evasion of mobilization (Articles 335-337) and military criminal offenses that may be related to unwillingness to fight or use weapons (Articles 402, 407-409).

- As well as a number of articles from the group “Crimes against peace, humanity, and public order” (Article 436, all parts). This group also includes articles on “Genocide,” “Ecocide,” “Violation of the laws and customs of war,” etc. The latter (Article 438) has seen the highest number of cases opened over the past three years, but they relate directly to combat actions and are not considered in this analysis.

Tens of thousands of cases have been opened for evasion of mobilization, desertion, illegal transportation of persons across the border, or illegal border crossing, which is closed to men of conscription age. These violations of the law are related to people’s unwillingness to fight and their attempts to avoid being sent to the front by any means possible. Over 138,000 cases have been initiated over three years on charges related to evasion of mobilization and desertion from the army, and over 6,500 criminal proceedings concerning assistance in illegal border crossing of Ukraine.

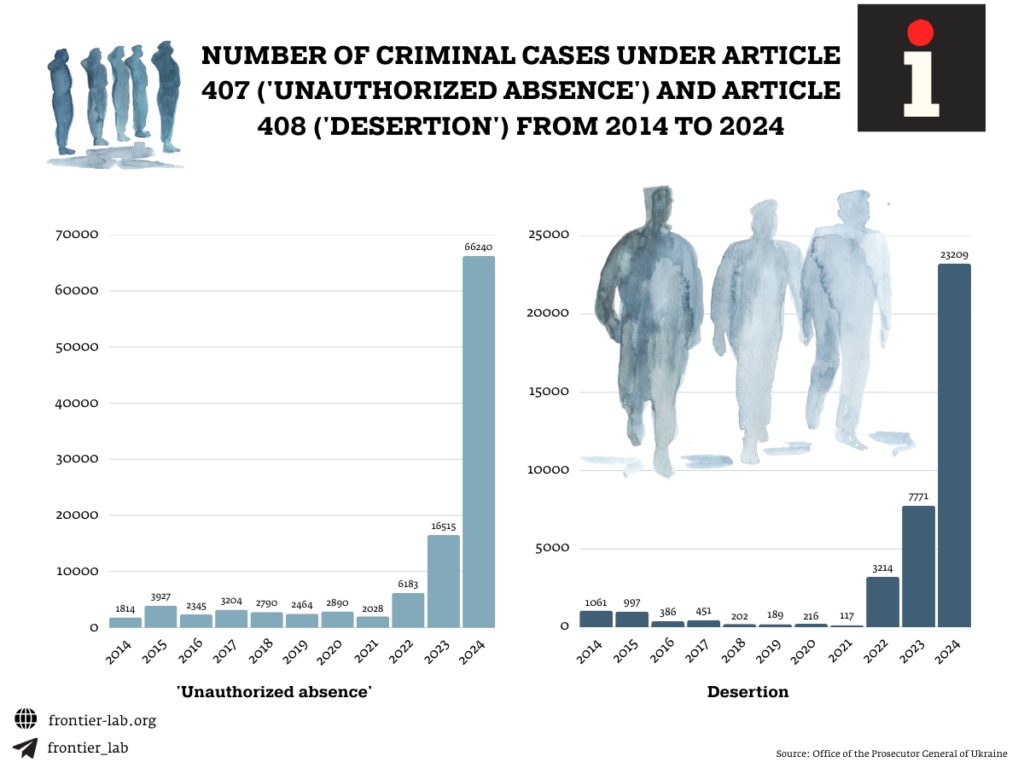

Articles 407 (self-abandonment of a military unit) and 408 (desertion) show a colossal increase, indicating a mass unwillingness of citizens to participate in hostilities. Under Article 407, the number of cases increased 11-fold – from 6,000 in 2022 to 66,000 in 2024. Under Article 408 – from 3,000 in 2022 to 23,000 in 2024.

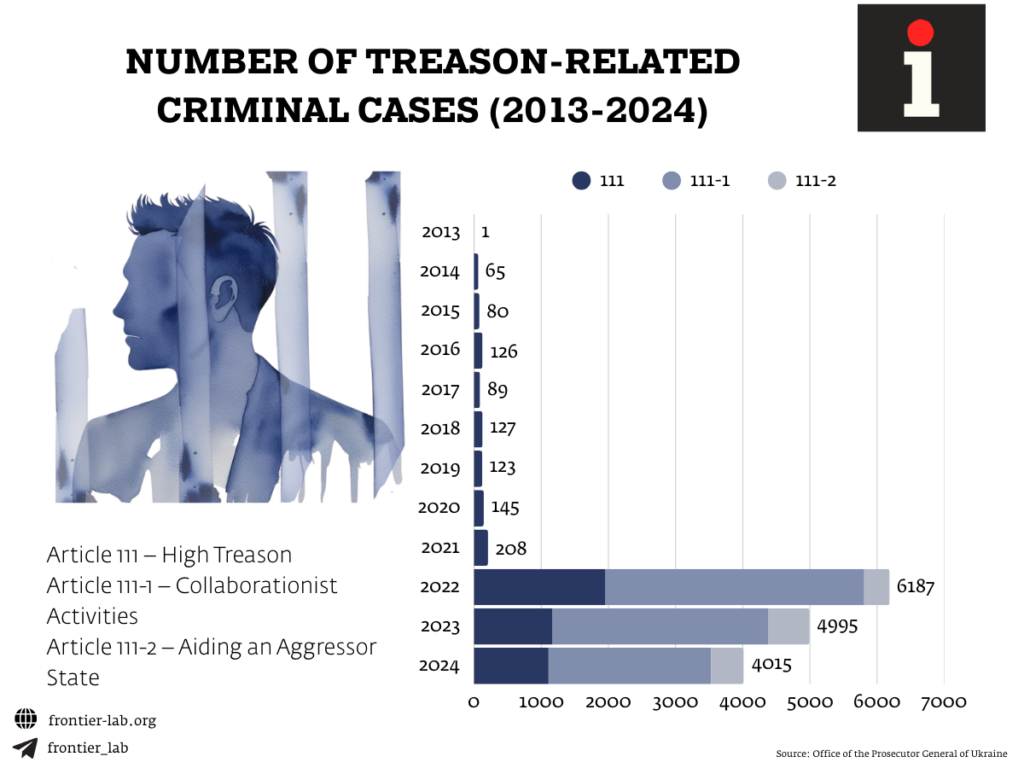

The number of criminal proceedings potentially linked to views and opinions has increased tenfold. For example, nearly 30,000 cases were opened between 2022 and 2024 on suspicion of committing crimes threatening national security. For comparison, approximately 1,300 proceedings were opened in the three years preceding the full-scale conflict. Between 2014 and 2021, there were 3,300 cases. Before the Maidan Revolution, there were only 7.

For instance, over 4,000 cases were initiated under Article 111 (high treason), and more than 11,000 under Article 110 (encroachment on territorial integrity).

Prosecutors are actively applying Criminal Code articles introduced/amended after 2022. For example:

- Article 436-2 (Justification of Russian Aggression): 3,600 cases opened in three years

- Article 111-1 (Collaborationist Activities): Nearly 9,500 cases

- Article 111-2 (Aiding an Aggressor State): 1,400 cases

- Article 114-2 (Disclosing Movement of Ukrainian Armed Forces/Weapons): Over 600 cases

Those accused under these articles often include active members of civil society (politicians, officials, clergy of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, entrepreneurs, lawyers, volunteers), as well as citizens who expressed sympathy for Russia, doubted the official Ukrainian explanation of the conflict, or had contacts with relatives in Russia.

Examples from last year:

The SBU detained 51-year-old Kyiv resident Mykola Istratov. He allegedly claimed on TikTok that Russia was not to blame for the Bucha tragedy, that the Armed Forces of Ukraine were shelling Donbas, and that the authorities had organized a genocide of the Russian-speaking population. Mykola now faces up to 8 years under Article 436-2 (justification of Russian aggression).

The SBU in Kyiv arrested music teacher Denys Pikulyk. The SBU press service claims he “mocked and ridiculed the fallen heroes on Maidan Nezalezhnosti.” Denys was charged under Article 436-2 of the Criminal Code (justification of Russian aggression) and sent to pre-trial detention without the possibility of bail. Pikulyk faces 8 years imprisonment. In his videos (publicly available), Denys did not humiliate or ridicule anyone. He showed propaganda banners with swastikas of the “Azov” and “Kraken” battalions placed in Kyiv, calling these groups Nazis. Regarding the fallen, he said that the war could have been stopped in Istanbul in 2022, but this is now forgotten.

The SBU detained a former employee of the Kupyansk city council (Kharkiv region), Artem Kovalenko, who continued to work in the local administration as a chief specialist in the construction department while the city was occupied by the Russian Armed Forces. His work involved the restoration of damaged buildings and structures. Kovalenko was charged under Part 2 of Article 111-1 (collaborationism) for this work. He faces up to 10 years imprisonment with confiscation.

Dynamics of Sentences with Actual Imprisonment

According to data from the Ukrainian court system, nearly 13,000 people have been convicted over three years under all articles related to the conflict (from expressing opinions to evasion of mobilization). Almost 3,500 sentences involve actual imprisonment.

Examples of recent sentences involving imprisonment:

Valeriy Beskurny from the village of Savintsy, Izium district, Kharkiv region, received 5 years under Part 5 of Article 111-1 (collaborationism). His only guilt is that from June 2022, he headed the housing and communal services sector in his village during the occupation by the Russian Armed Forces. Ensuring the operation of the housing and communal services sector is necessary for the survival of the population. According to the Geneva Conventions, the occupying party is obliged to involve representatives of the local population in such tasks. The other party to the conflict has no right to hold such people criminally liable. The Ukrainian law on collaborationism (Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code) contradicts Article 51 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, which prohibits holding civilians accountable for performing administrative functions in occupied territories if their actions did not harm the civilian population.

Roman Zavoloca, a fitness trainer from Poltava, was sentenced to 6 years with confiscation for publicly accusing the Armed Forces of Ukraine of “killing the fraternal people” and provoking Russia, which led to the war, in the summer of 2023. Photographs published after his arrest showed him severely beaten.

Lviv opposition activist Inna Ivanochko received 13 years for “high treason.” She was accused of participating in scientific-practical conferences, seminars, and street protests demanding a special economic and cultural status for Galicia in 2015. Before 2022, Ivanochko’s activities as a public opposition politician were not considered illegal.

Sixteen life sentences have been handed down in the past three years. For example, 22-year-old Angelina Dovhnia received a life sentence for allegedly providing an unspecified “Russian officer” with the coordinates of Armed Forces of Ukraine facilities. The verdict does not specify any victims or material damage, although the data on strategic facilities was provided to the “Russian officer” for a whole month, and the charges are based on the claim that the data was transferred specifically for missile strikes. The lawyer even asked this question in court, but the prosecutor ensured the court dismissed it. Furthermore, according to the case materials, the SBU monitored the girl from her first contact with the “Russian officer,” allowed her to transmit data six times without hindrance, and only then detained her. All this suggests that the crime was provoked by the SBU and was not actually committed.

The acquittal rate for conflict-related charges is extremely low — just 0.05% of all verdicts. Over the past three years, only 8 individuals were acquitted out of 15,700 convictions under these articles. For comparison, Ukrainian courts issued 235,000 final verdicts across all Criminal Code articles during the same period, with just 541 acquittals — resulting in an overall acquittal rate of 0.23%. While this general rate remains low by international standards, it is still nearly five times higher than the rate for politically sensitive conflict-related cases. Ukraine’s judicial system has long exhibited a strong conviction bias, but in cases involving treason, collaboration, or other conflict-related charges, additional factors compound the problem — including overt political pressure on judges, systematic denial of defendants’ rights to proper legal defense, and demonstrable prejudice within the court system when handling politically charged cases.

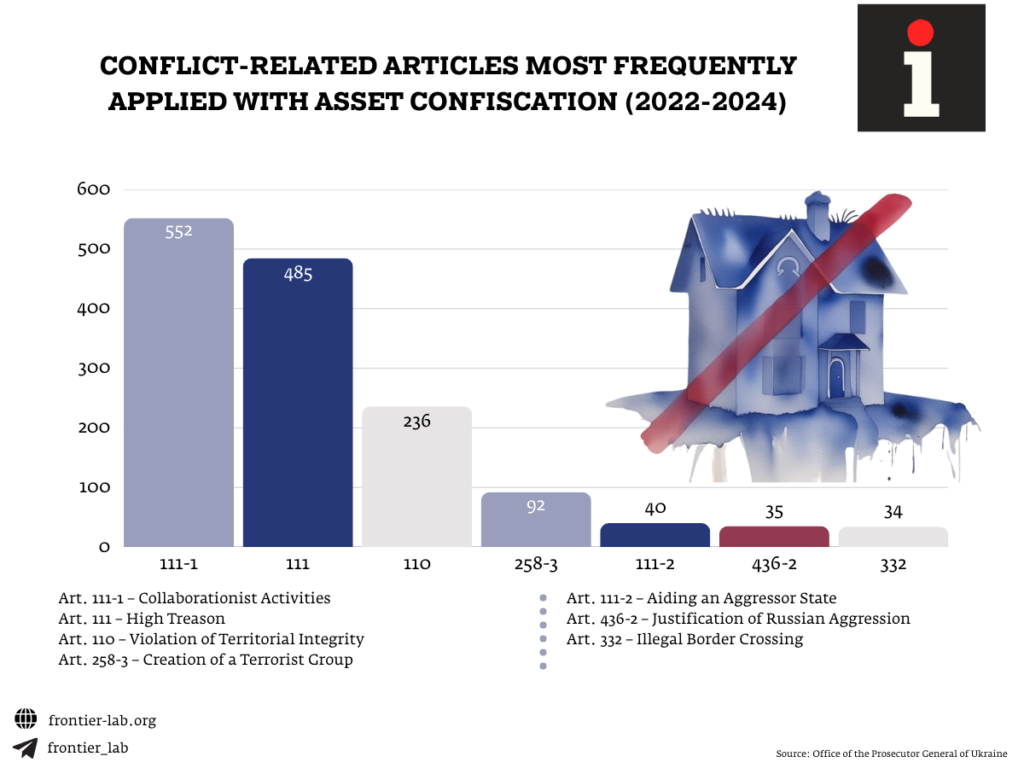

At the same time, among those convicted, there are 1,500 cases of confiscation of property and 338 cases of special confiscation, i.e., seizure of property from third parties. This means that confiscation was applied in almost every second sentence involving imprisonment and accounts for almost 10% of the total number of sentences under articles related to the conflict. This could be a way to pressure “disloyal” citizens.

General Trends

The number of sentences involving imprisonment does not fully reflect the number of people who have served time in prison, as a person could receive a “lenient” sentence, for example, a suspended sentence after several months or years in pre-trial detention awaiting judgment. Furthermore, some people who have already been charged are still awaiting trial in pre-trial detention. Nevertheless, the number of people deprived of their liberty in connection with charges under articles related to the conflict over three years amounts to several thousand people (possibly around 10,000). Some of these individuals are held in illegal detention facilities without proper procedural formalities.

Cases of torture and ill-treatment of detainees in politically motivated cases are common.

Broad interpretations of articles of the Ukrainian Criminal Code related to the conflict prevent citizens from predicting what actions might lead to criminal prosecution. This violates basic principles of legal certainty.

Lawyers’ work is hampered because they are criminally prosecuted for defending political prisoners. For example, Kyiv lawyer Svitlana Novitska and Kharkiv lawyer Volodymyr Yevhlevskyi are currently in pre-trial detention.

Politically motivated persecution and mobilization are leading to mass migration and a worsening social situation in the country. According to UN data, 1.2 million of Ukraine’s 6.9 million refugees have fled to Russia—despite Kyiv’s official narrative framing Russia as the aggressor state. Russia is presented as the aggressor state. The hunt for “traitors” creates an atmosphere of fear and intolerance.

Number of Criminal Proceedings and Convicted Individuals under Certain Articles of the Ukrainian Criminal Code Related to the Conflict, 2022-2024

| Criminal Code Article | Article Title | Cases Opened (2022-2024) | Cases Sent to Court with Indictment | Convictions (persons) | Imprisonment (up to life sentence) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109 | Actions aimed at violent change/overthrow of constitutional order or seizure of state power | 298 | 123 | 55 | 10 |

| 110 | Violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity | 11 606 | 300 | 393 | 294 |

| 110-2 | Financing violent constitutional changes or border alterations | 449 | 16 | 17 | 5 |

| 111 | High treason | 4 235 | 1 017 | 590 | 581 |

| 111-1 | Collaborationist activities | 9 478 | 2 457 | 1 487 | 649 |

| 111-2 | Aiding an aggressor state | 1 484 | 123 | 49 | 47 |

| 113 | Sabotage | 348 | 42 | 2 | 1 |

| 114 | Espionage | 107 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| 114-1 | Obstructing Ukraine’s Armed Forces | 1 075 | 182 | 84 | 7 |

| 114-2 | Unauthorized disclosure of military movements/weapons transfers | 605 | 258 | 163 | 96 |

| 258 | Terrorist act | 160 | 13 | 18 | 18 |

| 258-2 | Public calls for terrorist acts | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 258-3 | Creating terrorist groups/organizations | 361 | 159 | 131 | 126 |

| 258-4 | Facilitating terrorist acts | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 258-5 | Terror financing | 73 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 260 | Creating illegal paramilitary groups | 437 | 163 | 16 | 9 |

| 332 | Illegal border crossing | 6 632 | 2 784 | 558 | 91 |

| 332-1 | Illegal entry/exit to occupied territories | 26 | 9 | 7 | 1 |

| 332-2 | Unauthorized border crossing | 117 | 39 | 36 | 7 |

| 335 | Draft evasion (regular service) | 36 | 27 | 122* | 1 |

| 336 | Mobilization evasion | 9 039 | 3 897 | 1 734 | 278 |

| 336-1 | Civil defense service evasion | 120 | 7 | 15 | 2 |

| 337 | Military registration evasion | 577 | 471 | 331 | 1 |

| 402 | Insubordination | 5101 | 1 141 | 1 581 | 81 |

| 407 | Unauthorized absence from service | 88 938 | 5 425 | 3 541 | 688 |

| 408 | Desertion | 34 194 | 529 | 438 | 202 |

| 409 | Military service evasion via self-harm | 654 | 150 | 114 | 10 |

| 436 | War propaganda | 91 | 45 | 9 | 0 |

| 436-1 | Communist/Nazi symbolism propaganda | 877 | 513 | 221 | 23 |

| 436-2 | Justifying Russian aggression | 3 659 | 1 664 | 979 | 139 |

| Total cases related to the conflict (excluding direct combat actions) | 180 786 | 21 563 | 12 700 | 3 372 |

*The number of convictions under Article 335 over the three years of conflict indeed exceeds the count of initiated criminal cases for the same period. This discrepancy stems primarily from 2022 data, when 112 individuals were convicted under this article—despite most cases having been opened prior to the full-scale invasion. Before the conflict, several hundred cases under this statute were registered annually.

This translation was made using a neural network. If you find any inaccuracies, please contact us.